by Inga Leonova

- Louis Kahn, Monumentality

Holy

Trinity Cathedral in Boston occupies a fairly unique place in the

history of Orthodox architecture in the North American Metropolia.

Built in the years preceding the granting of autocephaly to the

Orthodox Church in America, it is in many ways a testament to the

attempt of the descendants of the Russian mission to express their

emerging American Orthodox identity in the context of broader

American culture. The

history of church architecture in America reflects in wood, brick,

stone and concrete the turbulent history of the establishment and

development of Orthodoxy in America. The first missionaries in Alaska

began by resorting to the tradition of house worship of the early

years of Christianity, establishing chapels in houses of the Russian

American Company and later, as the mission expanded, in homes of the

converted native Alaskans. The first church buildings naturally

repeated the architecture of the northern Russian wooden churches. As

the mission moved its headquarters into the mainland, first to

California and then to the East Coast, it carried with it the same

tendency to construct its houses of worship in the image and likeness

of churches of its homeland. Monuments of that time include the

original Holy Trinity Cathedral in San Francisco and St. Nicholas

Cathedral in New York, among others. However Original HTOC building in West Roxbury Interestingly

enough, westernized Orthodox architecture of post-Petrine Russia made

little mark on the architecture of the American Metropolia. Nostalgia

focused on the images of pre-Petrine structures. Where new churches

were built from the ground up, with some capital to spare, their

design strove to repeat the familiar lines from clean whitestone

Vladimir/Suzdal ancient churches to the architectural richness of

Russian and Ukrainian baroque. Unfortunately,

nascent development of new architectural thinking which began in

pre-revolutionary Russia and which carried great potential for the

architectural development in the Metropolia was arrested and squashed

by the October revolution. For the multitudes of Russian and Eastern

European exiles, there was hardly any question of the need for

establishing American Orthodox architectural identity. Their desire

was for romanticized rolex replica uk traditional church architecture.

Post-revolutionary immigrants reacted with sometimes violent disdain

to the proliferation of cheaply constructed Orthodox churches in

America which utilized, like St. Gregory the Theologian Church in

Wappinger Falls, NY, or St. Stephen Cathedral in Philadelphia, PA,

typical “one size fits all” church blueprints prepared by

American architects with minimal Orthodox “customization”. One of

the most vocal critics of the disparity and lack of vision in

American church construction was an immigrant architect from St.

Petersburg Roman N. Verhovskoy. Verhovskoy was a curious figure. A

graduate of the Imperial Russian Academy of Art in St. Petersburg,

Verhovskoy aspired and eventually succeeded in establishing himself

as the official Architect of the Russian Metropolia. He vehemently

believed and professed that Orthodox architecture in America had one

purpose only, that of being the face of the Russian people in

America. In the words of his manifesto, “The church is the face of

the national soul (spirit) of each nation. Only persons deprived of

the deep feeling of their national dignity and self-respect

(personality) go toward other foreign people to beg them for their

“face” – image (project) of their own church, i.e. of their own

spirit, their own religion. As a result, the foreign, outside world

considers this kind of people as being a “lower race”

(emphasis in the original).1 In the

course of his long career in America, Verhovskoy was tireless in his

violent criticism of any Orthodox church architecture which deviated

in any way from what he considered the “golden standard” of

Russian Orthodox church building. The “golden standard” was, not

surprisingly, his personal vision, which, judging by several

surviving churches and drawings of unbuilt edifices, was a

romanticized and somewhat modernized version of Vladimir style, on

par with the explorations of the great Russian architect Alexei

Shchusev but nowhere near as elegant or sophisticated. In fact, the

analysis of his archive demonstrates that he sought to legislate his

oversight over every single architectural design in the Russian

Metropolia, and took as personal offense every project which was

undertaken without appealing to his expertise and advice. In spite of

such active campaigning for himself, his legacy includes only a

handful of churches, several iconostases and an unrealized project

for an All-American Cathedral which was intended to be built on the

site of the present Second Street Cathedral of Holy Virgin Protection

in New York. In conflict with his repeated statements that only

national architects should build national churches, he undertook two

projects for the Greek Archdiocese and even a Buddhist temple. Never was

his criticism so vitriolic, however, as when the offending architect

was striving to explore the vernacular legacy of American

architectural landscape and develop the archetypes that would go

beyond the repetition of familiar ancient forms from the “old

country”. His comments on those projects are not for the faint of

heart to read. One of his favorite targets, perhaps due to his

practicing in the vicinity of Verhovskoy’s own studio in New York,

was a Boston architect Constantine Pertzoff. Constantine

A. Pertzoff was also a White Russian immigrant from a similar

background as Verhovskoy, yet being some years Verhovskoy’s junior,

his formation as an architect occurred in his new homeland. He was a

graduate of Harvard Graduate School of Design at the time when

austere Bauhaus2 Modernism brought from Germany by Hitler’s exiles was triumphantly

conquering the minds of young American architects. He went on to

become a friend and colleague of one of the greatest Bauhaus

architects Walter Gropius, the founder of the famous Boston office of

“gentlemen architects” from Europe The Architects Collaborative

(TAC). His professional legacy includes several houses, his own among

them, in the Modernist colony in Lincoln, MA, a fairly well-known

1944 master plan for the redevelopment of Manhattan, and a small but

interesting collection of writings, especially notable for his

forward-thinking notions on sustainable architecture. By virtue of

being a parishioner of Holy Trinity Cathedral, in 1948 Pertzoff

received a commission for the design of the new cathedral on Park

Drive, which led to at least two more known church projects in

Ansonia, CT, and Waterbury, CT. The church of St. Nicholas in

Whitestone, NY, designed by Sergey Padukow, who became a successor of

sorts to Roman Verhovskoy as the spokesperson for the architecture of

the Metropolia, exhibits interesting parallels with the design of

Holy Trinity. U

The

design and erection of the new Holy Trinity Cathedral was truly a

fruit of the long and laborious “penny collection” among the

parishioners, a term coined in the early years of the Metropolia to

signify participation by all members. Initially the parish bought a

building in Roxbury from the Congregational Church. Funds for the new

building started to be collected at least as early as mid-1930s, but

collections were slow and accompanied by much internal controversy.

The arrival of Fr. Chepeleff in 1941 gave a new boost to fundraising

efforts. Fr. Chepeleff’s considerable fundraising talents resulted

in the rapid growth of the building fund, although large donors were

still few and far between. The groundbreaking ceremony, presided over

by Bishop Dmitri (Magan) of Boston and Fr. Chepeleff took place on

September 25, 1949, but parish documents from as late as November of

1950 record that construction could not start until at least 75% of

the bid price of $119,000 could be guaranteed. In 1950, in the midst

of considerable controversy, Fr. Eugene Survillo replaced Fr.

Chepeleff as rector of HTOC. The ensuing strife between parish

factions further complicated financial issues. At the parish meeting

in July of 1951 Bishop Dmitri took matters in his own hands and

called on each member to stand up and say how much they were going to

give or lend towards ongoing construction. Meeting minutes record

each and every name and amount. Donations were primarily around

$50-$100, with a single pledge of $1,000 and one $500 loan.

Signing of HTOC construction contract, 1950. Walter Gorelchenko, AJ Martini, Due to

lack of additional funds, the construction of the iconostasis did not

begin until at least 1968. The original design called for painted

icons, but subsequently a decision was made to create mosaics and

commission them from Baron Nicholas B. Meyendorff, an iconographer

residing in Vienna, Austria. Special collections were taken to cover

the cost of each mosaic icon. In June of 1969 Nicholas Meyendorff

unexpectedly passed away, and the mosaics that had already been

started were completed by his daughter Helen. Ten out of the planned

twelve mosaics of the Apostles were eventually completed and

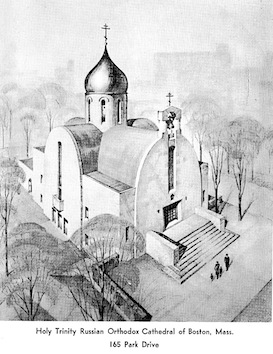

installed. Architectural design of Holy Trinity Cathedral on Park Drive was completely unique in the fabric of Orthodox architecture, American or otherwise. Pertzoff attempted to synthesize his knowledge of traditional Russian ecclesiastic architectural forms (cruciform, barrel vaults) with the motifs of New England ship design, whereby the structure of the building employed glued laminated wood beams as barrel ribs and wood planking as its skin, evoking the imagery of a ship’s hold which refers both to seafaring traditions and to the ancient Christian image of church building as a ship. Pertzoff’s Modernist foundation is evident in the simplicity of the main volumetric solutions as well as the use of light yellow brick which, in contrast to the traditional Boston red brick, was a very popular Modernist material of the day. In a rather charming nod to his Modernist friends, Pertzoff used the same pendant light fixtures in the cathedral hall and wall sconces in the nave that had been used by Gropius in his projects at Harvard Law School and his own house in Lincoln.

Whether this synthesis was completely successful is a matter of opinion. It seems that in his church projects Pertzoff usually achieved better results in his design of interior spaces. The cruciform barrels of the Holy Trinity Cathedral, completely uninterrupted due to load bearing structural properties of laminated wood, form a glorious open space which bestows the feeling of awe and the soaring of the spirit on a newcomer. The use of natural wood allows for a more intimate feeling of the space than would be presumed by its physical size. The abundance of natural light and the placement of the windows afford a dynamic and sometimes mystical quality to the space which enriches the experience of liturgical services. The absence of interior divisions in the nave, save for the iconostasis which separates the main space from the sanctuary, conveys the “oneness” of the church community in the celebration of the Liturgy.

Regardless of matters of personal taste, Holy Trinity Cathedral is recognized as a Boston architectural Modernist landmark and is featured as such in the American Institute of Architects' Guide to Boston (in an entry which also mentions the installation of Bishop Nikon as the ruling bishop of Boston and New England at the HTOC in 2005).

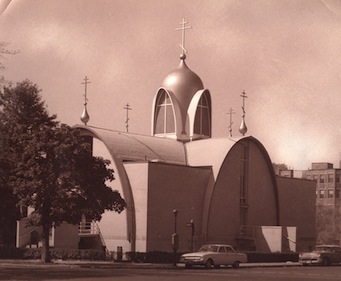

Newly-completed Cathedral with the original dome, 1960

Contemporary

view of the Cathedral |

1From the preparatory documents for the Eighth All-American Orthodox Church Council, 1950. Grammar and spelling are preserved from the original. 2Bauhaus was a design school in Germany founded by Walter Gropius that combined crafts and the fine arts. It operated from 1919 to 1933. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design. 3 Later Mother Alexandra, founder of the Holy Transfiguration Monastery in Ellwood City, PA. |

nlike

many of his compatriots, Pertzoff had been so successfully

assimilated into the American society that in 1937 he married Olga

Monks, a niece of Isabella Stewart Gardner, in a three-stage ceremony

which included two religious services (one in Holy Trinity Cathedral

presided over by Fr. Jacob Grigorieff, and one in a Episcopal Church)

and a reception in the Gardner palazzo across the park from the

future site of the new cathedral. According to family history, this

connection proved highly advantageous to the Holy Trinity parish when

in the 1940s Fr. Theodore Chepeleff and his son Valentin were

crisscrossing Boston in their search for a site for the new

cathedral. Apparently the family of Pertzoff’s wife had assisted

the parish in their negotiations for the site at 165 Park Drive which

resulted in the purchase price of $17,000, considerably lower than

the 1948 going market rate in the neighborhood. According to parish

documents, Pertzoff, in addition to being the architect for the new

cathedral and its iconostasis, was also one of its most significant

donors, which allowed him to exercise considerable freedom in making

decisions and wielding significant power in his relationship with the

cathedral building committee.

nlike

many of his compatriots, Pertzoff had been so successfully

assimilated into the American society that in 1937 he married Olga

Monks, a niece of Isabella Stewart Gardner, in a three-stage ceremony

which included two religious services (one in Holy Trinity Cathedral

presided over by Fr. Jacob Grigorieff, and one in a Episcopal Church)

and a reception in the Gardner palazzo across the park from the

future site of the new cathedral. According to family history, this

connection proved highly advantageous to the Holy Trinity parish when

in the 1940s Fr. Theodore Chepeleff and his son Valentin were

crisscrossing Boston in their search for a site for the new

cathedral. Apparently the family of Pertzoff’s wife had assisted

the parish in their negotiations for the site at 165 Park Drive which

resulted in the purchase price of $17,000, considerably lower than

the 1948 going market rate in the neighborhood. According to parish

documents, Pertzoff, in addition to being the architect for the new

cathedral and its iconostasis, was also one of its most significant

donors, which allowed him to exercise considerable freedom in making

decisions and wielding significant power in his relationship with the

cathedral building committee.